Film

120 Bahadur Movie Review: Farhan Akhtar’s Film on the Rezang La Battle, there are battles within it

That insistence alone gives 120 Bahadur a significance that extends beyond the screen — even when the film itself struggles to match the weight of the story it tells.

When a Hindi war film returns to the 1962 India-China conflict, expectations are inevitably heavy. That burden is even greater when the story centres on the Battle of Rezang La — a last stand by 120 soldiers of the Indian Army that has lived on more in oral history and military folklore than in popular culture. 120 Bahadur, starring Farhan Akhtar as Major Shaitan Singh Bhati, sets out to reclaim that story for a new generation. In doing so, it becomes a film of sharp contrasts: between restraint and excess, tribute and trope, history and cinematic habit.

Produced by Excel Entertainment and directed by Razneesh “Razy” Ghai, 120 Bahadur revisits the night of 18 November 1962, when Charlie Company of the 13 Kumaon Regiment defended the Rezang La pass in eastern Ladakh against a vastly superior Chinese force. Fighting at altitudes above 16,000 feet, poorly equipped for extreme cold and outgunned, the soldiers held their ground until almost all were killed. Major Shaitan Singh was posthumously awarded the Param Vir Chakra, India’s highest military honour.

The film positions itself as a corrective — not only to historical amnesia, but also to the loud, chest-thumping nationalism that has come to dominate Bollywood’s war genre. The enemy is not Pakistan, the setting is not a familiar desert or border village, and the men at the centre are largely from the Ahir community, farmers from the plains facing an alien, frozen battlefield. There is even an acknowledgement, rare for the genre, that for years doubts were raised about whether such a battle had occurred at all — doubts dispelled only when the battlefield was later discovered, frozen in time.

At its best, 120 Bahadur honours this history with sincerity. The decision to frame the story through the memories of Ramchander, the radio operator and one of the few survivors, is among the film’s most compelling ideas. His testimony — once questioned, later vindicated — becomes a metaphor for how truth survives war, politics and revisionism. In an era of contested narratives, the idea of a lone storyteller holding the line between remembrance and erasure feels timely and resonant.

The film is also strongest once it commits fully to the battlefield. The extended final act, depicting the last stand at Rezang La, captures the sheer physical and emotional toll of combat at high altitude. Shot by cinematographer Tetsuo Nagata, the Ladakh landscapes are stark and unforgiving, and the secondary cast — many of them relatively unknown — bring conviction to the roles of ordinary infantrymen bound by camaraderie rather than rhetoric. Their heroism emerges less from speeches than from persistence: advancing despite frostbite, injuries and hopeless odds.

Yet for much of its runtime, 120 Bahadur struggles to escape the very conventions it appears eager to reject. The filmmaking language is familiar to the point of fatigue: swelling background scores, tight close-ups that flatten scale, slow-motion combat, and dialogue that often sounds written for a contemporary audience rather than soldiers in 1962. Patriotism frequently slides into declaration, with repeated reminders of identity, origin and sacrifice taking precedence over quieter character detail.

The portrayal of the Chinese soldiers is another sticking point. Reduced largely to faceless, sneering antagonists, they exist to underline Indian virtue rather than to reflect the complexity of war. Visual contrasts — frugal Indian meals cut against lavish enemy feasts, humble soldiers against caricatured commanders — are driven home with little subtlety. The result is a moral universe in which goodness is defined less by humanity than by the villainy of the other side.

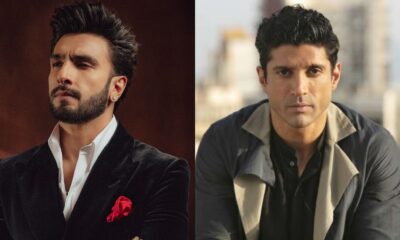

Farhan Akhtar’s casting as Major Shaitan Singh has drawn the most debate. Earnest and controlled, Akhtar approaches the role with respect, but for some viewers his urbane presence and age make it difficult to fully inhabit a 37-year-old frontline officer from rural Rajasthan. His Major Singh convinces more through action than oratory, and while the performance avoids excess, it never quite disappears into the role. Raashii Khanna, as Singh’s wife Sugan, brings warmth in a limited part, though personal backstories — including songs and festive interludes — sometimes feel superfluous against the urgency of the larger narrative.

The film is also not immune to repetition. War cries, clan references and speeches about land — zameen and sarzameen — are thematically sound but overused, occasionally overshadowing the individuality of the men themselves. Earlier films such as Chetan Anand’s Haqeeqat (1964), inspired by the same battle, found universality without foregrounding identity so insistently. That comparison is perhaps unfair, given the vastly different political and cinematic climates, but it lingers.

Still, 120 Bahadur remains consistently watchable because its intent is never in doubt. It does not mock its subject, nor does it trivialise sacrifice. If it errs, it does so by insisting too loudly on emotions the story already earns. The film’s paradox mirrors that of the war genre itself: it seeks to honour sacrifice while relying on spectacle; it demands reflection while resorting to amplification.

In the end, 120 Bahadur may not fully transcend the limitations of mainstream Hindi war cinema, but it performs an important act of remembrance. By returning Rezang La to public conversation, it reminds audiences that while India lost the 1962 war, there were battles within it defined by extraordinary courage. More than victory or defeat, the film insists on one truth: that these soldiers fought, held their ground, and refused to be forgotten.

That insistence alone gives 120 Bahadur a significance that extends beyond the screen — even when the film itself struggles to match the weight of the story it tells.